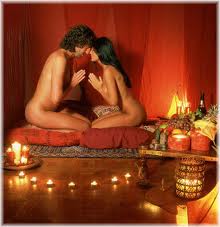

Promising physical and spiritual ecstasy, Tantra workshops lure couples who want more from their relationships. But what really goes on?

By Todd Jones

Bill and Susie McKay grew up in the same small Southern town. His father was a military man; hers was a Baptist preacher. Duty was an important word in both of their households, and it applied to just about everything—including sex. “I grew up with the message that sex was a duty that a wife does for her husband,” Bill says. “That didn’t seem quite right, but I didn’t know anything different.”

“For a long time, I hadn’t been happy with our sex life,” Susie chimes in. (Names and some biographical details have been changed to preserve subjects’ privacy.) “We were still pretty much repeating what we did 25 years ago when we were inexperienced kids. It reached a point where there wasn’t much for me to like. Then a friend started telling me about these Tantra workshops. At first I was reluctant, and then one day everything just dropped into place and I knew I wanted to go. I didn’t just want sex, I wanted to connect with both my heart and my second chakra—to have an open heart in a loving, sexual act. And a Tantra seminar seemed like the perfect place to learn.”

In the past, couples like Bill and Susie might have sought to infuse more love and passion into their marriages by consulting a minister, a priest, or a rabbi. In the first half of this century, they might have consulted a psychoanalyst; beginning in the ’60s, they might have made an appointment with a sex therapist armed with the research data of sexologists like William Masters and Virginia Johnson. All those options are still available. But over the last couple of decades an increasing number of Americans and Europeans have turned instead to books, videos, and seminars with such titles as Spiritual Sex, The Art of Sexual Ecstasy, The Love and Ecstasy Training, and Tantra: The Art of Conscious Loving. These teachings claim to fuse sex and spirituality in a transcendent mix that can transform sexual relationships into both physical ecstasy and a path to personal growth, liberation, and enlightenment.

Seekers exploring a consciously spiritual approach to sex are not just motivated by sexual dissatisfaction. Many already have fulfilling sex lives, but sense that sex and relationship have the potential to provide them with deeper experiences of connection with each other and with the cosmos. Others embark on a search for sacred sexuality after years of meditation in some Eastern tradition. These traditions offer time-honored methods of achieving spiritual growth and insight, but they offer scant wisdom on the subject of sexuality, since they have historically been practiced mostly by celibate monks and nuns.

The sacred sexuality teachings that have gained popularity over the past 20 years incorporate ideas and techniques from the human potential movement workshops that have been evolving since the ’60s, from pre-modern Taoist and Middle Eastern sexual teachings, from India’s extensive texts on the sexual arts (including the famous Kama Sutra), and from mainstream sex therapy. But, above all, the modern sacred sexuality movement draws its inspiration and techniques from the same ancient spiritual tradition of the Indian subcontinent that spawned most of the practices we now know as hatha yoga—the tradition known as Tantra.

Tantra Comes West

Tantra arrived on the cultural radar of mainstream America in 1989, with the publication of Margot Anand’s The Art of Sexual Ecstasy. But even before Anand’s ascent to the best-seller lists made Tantra a household word, other writers and workshop leaders had been mining Eastern sexual and spiritual techniques and blending them with elements of Western sexology, psychotherapy, and New Age self-transformational techniques. One of the first of these was Charles Muir, a yoga teacher who had been a follower of Swami Satchidananda until he became disillusioned by revelations of Satchidananda’s illicit sexual relations with some devotees. He then spent time as a student of Swami Satyananda, and as a teacher in the tradition of TV yoga guru Richard Hittleman.

After his first marriage, Muir began to reexamine his ways of relating with women, and, as he puts it, “was blessed with the teachings of a number of remarkable women” who initiated him into their knowledge of Tantric sexuality. Muir also started to study the ancient Tantric texts, and began including more and more such teachings in his yoga workshops. By 1980, Muir made a full-time switch from hatha yoga teacher to Tantric sexuality teacher. Two decades later, he and his wife Caroline are still probably the best known teachers of Western Tantra.

On the first night of the Muirs’ weeklong workshop entitled “The Art of Conscious Loving,” at the Rio Caliente spa about an hour outside Guadalajara, Mexico, nine couples gather in a circle. The group seems subdued and a bit tense, with a palpable undercurrent of nervous anticipation.

Tom, a handsome psychologist born to Central American parents but raised mostly in the States, and his partner, a black-haired social worker with a mischievous grin named Leslie, emit a honeymoon glow as they sit entwined around each other. In contrast, Susie’s back is turned like a stiff wall toward Bill, who hunches as though he’s trying to take up as little space as possible. Stan and Liz, an outgoing pair of 67-year-olds from a wealthy Southern California suburb, chatter about their upcoming nuptials—”the second for both of us,” Stan says, “but we’re telling people it’s our first real marriage.” Next to them Anja, a native of Denmark and a healer, and Merle, her American partner, seem the most relaxed pair as they sit quietly with placid, taciturn smiles.

The couples are almost as diverse occupationally as geographically—no blue collar workers, but, for such a small group, a fair slice of middle and upper middle class white America: a retired government bureaucrat now doing volunteer work; several entrepreneurs, an architect, a secretary, a teacher, an accountant, and a disproportionate number of healers of various types—a doctor who specializes in alternative/complementary medicine, the psychologist and the social worker, an art therapist, and four bodyworkers/energy healers. Quite a few turn out to be committed to Eastern spiritual practices. The doctor practices Zen; for several years he attended asesshin, an intensive meditation retreat, for one week out of every two months. Anja started and ran a yoga school for 17 years, closed it to open a school of esoteric energy healing, and finally lived alone in the woods for six years of intense personal spiritual practice. Merle, who runs a bodywork school, has practiced vipassana meditation for several years. Another bodyworker mentions a decade-long association with Yogi Bhajan’s Kundalini Yoga community.

Later, when Charles asks each couple to share what drew them to this Tantra workshop, Anja reports that she was so inspired by a visit to the Tantric temples at Khajuraho, in central India, with their relief carvings of hundreds of ecstatically (and acrobatically) entwined lovers, that she swore to some day find a man with whom she could share Tantra. Now, she says, after 12 years of celibacy, she has. Two participants attended the workshop previously and have returned to share it with a newfound soul mate. On the whole, though, the couples seem quite reluctant to talk publicly about their sexual lives. Yet, traveling from as far away as Hawaii and Denmark and anteing up $3,400 per couple (plus airfare), they have all committed a substantial investment of time, money, and energy to their relationships—and to the exploration of Tantra.

The Muirs begin by contrasting the sexual education—or, more accurately, the lack of it—most Westerners receive to the more respectful, celebratory, and unconflicted attitudes they attribute to ancient Indian culture. With his characteristic humor and earthy language, Charles offers up as fairly representative his teenage tutelage with the leader of a Bronx street gang in the 1950s: “‘Get it hard, get it in, and get it off. Fuck ’em hard and fuck ’em deep.'” Many of us, Charles points out, receive little more information than this about the vast possible joys of sexual loving. “We learn most of what we know about intimacy from those great fonts of wisdom and experience, dear old mom and dad,” Charles says, drawing snorts of rueful laughter from the group. Outside our families, we glean information—often misinformation—from the locker-room talk and slumber party whispers of our peers, and we absorb intensely mixed messages from the adults, religious institutions, and pop culture around us. “How can you not be confused” asks Charles, “when you’re told both ‘Sex is dirty’ and ‘Save it for the one you love?'”

Caroline picks up the thread, pointing out that many of us also approach adult sexuality scarred by childhood and adolescent experience of incest or other sexual abuse. When we finally find partners for our first sexual explorations, often as not we end up with further emotional wounds from fumbling in the dark with lovers as misinformed, ignorant, and scarred as ourselves. “Is it any wonder,” Caroline asks rhetorically, “that many of us don’t really know how to ‘make love?’ We may have learned how to get off, but not how to use sex to make more love in our relationships.”

As models of a healthier attitude, Caroline holds up ancient cultures, especially that of India. She points out that Indians revered sexuality as a holy gift from the creator, regarding sex as both a sacrament and an art form, celebrating it in their art, and teaching its secrets to their children. Sex was used not just to join two lovers, but as a meditation through which the lovers could unite with the divine energy of the universe. “This week,” she says, “we’ll learn how to make sex be sacred again.”

The Yoga of Relationship

Before adjourning for the evening, Charles outlines the three interwoven topics he and Caroline will be teaching throughout the week: increasing energy and pleasure; increasing intimacy; and quieting the mind. “We’ll learn many techniques for increasing the energy and pleasure you can feel in your body,” he says. Many of the techniques will be what he calls White Tantra—practices that can be done individually, like asana, pranayama, repetition of mantras—while others will be Red Tantra—practices that involve joining your energy with a partner’s.

Techniques for fostering intimacy, Charles says, are designed to allow lovers to increase their ability to give and to receive each other’s energy. He adds that workshop participants will discover that they don’t need to learn to do more; they simply need to surrender and allow themselves to be who they naturally are. In the end, says Charles, “Relationship is the ultimate yoga. If you’re in a relationship, it is a yoga, a spiritual pathway. Relationship will bring up every lesson you need to learn.”

All these techniques culminate, he emphasizes, in the quieting of the mind. Instead of habitually using the thinking mind, students will learn to cultivate the mind’s capacity for being completely quiet and receptive. “Ultimately, Tantra is a meditation,” Charles notes. “In fact, orgasm is the only universally shared meditative experience, the one that cuts across all cultures. At the moment of orgasm, you’re not in your thinking brain, you’re in your receptive, being brain; when you’re completely absorbed in the present, you enter into timelessness.”

As the week progresses, some of the information and exercises are explicitly sensual and sexual. Participants are given primers on touch, kissing, and oral sex, on using the breath to intensify and prolong orgasm, on strengthening the pubic-coccygeal muscles to increase sexual pleasure. One session especially directed at the men focuses on a number of methods for delaying (and heightening and lengthening) orgasm. Using hand puppets—an oversized, furry yoni and lingam(respectively, the Sanskrit names for female and male genitalia)—Charles and Caroline demonstrate how to use your hands to delight your partner, how to mutually pleasure each other using a man’s “soft-on” instead of a “hard-on,” and how to bring infinite variety to intercourse by changing the speed, depth, and angle of penetration. Inviting their students to gather around them, the Muirs conduct a graphic (though fully clothed) seminar on sexual positions, complete with detailed demonstrations of how to use pillows to support an aching back, and how to gracefully segue from front to side to back entry positions, and from woman on top to man on top and back again, without ever losing contact and intimacy.

Charles and Caroline also spend just as much time on techniques that are far more esoteric and far less explicitly sexual. Almost every day, they lead the class through a half-hour or more of gentle hatha yoga. The routines wouldn’t pose much physical challenge to any regular practitioner, but that’s not the Muirs’ focus. Instead, as in all the yogic techniques they teach, they emphasize awareness of the subtle energy body and the chakras. All the chakras, Charles says, contain dormant energy, consciousness, and intelligence, and the Tantra techniques he teaches aim to arouse and harness those latent energies. He stresses that the goal in doing these asanas shouldn’t be to achieve any particular stretch or outward form, but instead “to recognize and reconcile yourself with your body just as it is.”

“These asanas are not exercises,” Caroline chimes in, “they are poses: sacred geometries for awakening and becoming aware of energy.” As they lead a simple but well-rounded sequence (standing and balancing poses, side stretches, forward and backward bends), Charles and Caroline direct the participants to support the circuits of energy in the body with the breath: In a forward bend, for instance, students breathe energy up from the feet through the legs and torso and exhale it out through the crown of the head before beginning the cycle again with the feet.

The Muirs also give instruction in pranayama (breathing techniques), ranging from simple, full breaths to more advanced practices, such as using bandhas (energetic “locks”) to contain and heighten energy in the body, or directing energy up to the space between the third eye and crown chakras by using the rapid forced exhalations of “breath of fire” (Kapalabhati). The group intones various bija mantras, sacred “seed syllables” whose vibration is said to awaken each chakra; visualizes yantras, geometric diagrams that serve the same purpose; and practices mudras, potent hand gestures that create specific flows of energy. Along with all these solo yogic techniques, Charles and Caroline direct participants in breathing with a partner. First the class members practice simply coordinating and harmonizing their inhalations and exhalations. They go on to practice reciprocal breathing—in which each breathes in his or her partner’s energy as the partner exhales, and vice versa. Eventually, they use breath to link their bodies together in a circular flow of energy.

Sacred Spot Massage

Although the Muirs present an enormous range of information and lead many exercises, their workshop pivots on the practice they call “sacred spot massage.” In this intimate ritual, conducted by each couple in the privacy of their own room, the man will spend an entire evening in the role of sexual shaman, offering his partner the loving presence and touch that can help heal old wounds and allow her to open more completely into her full sexual power. (Later in the week, the couples reverse roles, with the women giving and the men receiving healing and empowerment.)

According to the Muirs, Tantra believes women’s sexual arousal and orgasm can open them to channel ever increasing amounts of shakti, the basic energy of the universe, which both she and her partner can then tap into. (Men, on the other hand, are said to have a more limited, less renewable store of sexual energy, which is depleted every time they ejaculate. For men, the key is not so much opening up to sexual energy, but instead learning to contain and experience an ever greater degree of energy and ecstasy without dissipating it through ejaculation.) “The knowledge of women’s limitless sexual potential has been lost to our culture,” says Caroline. She and Charles insist not only that all women are endlessly, naturally multiorgasmic, but that all are capable of both explosive clitoral orgasms and deeper, longer, more wavelike vaginal orgasms that can be accompanied by female ejaculation.

A key to fully awakening a woman’s sexuality, the Muirs say, is loving massage of the “sacred spot,” a region of highly sensitive tissue located about two inches up the front wall of the vagina. (In Western sexology, this is the “G-spot,” named for Ernst Grafenberg, the gynecologist who first described it in Western medical literature.) But along with previously unknown pleasures, sacred spot massage can also unleash memories of sexual confusion, repression, pain, and abuse. We don’t just store such memories in our minds, but in our bodies—and especially in the tissues around our second chakra (the genital region), which Tantra regards as the wellspring of our energy. The pain surrounding these memories must be addressed and released, the Muirs believe, before we can experience all the joy of unfettered sexual energy.

The Muirs stress that sacred spot massage should never be undertaken with the goal of orgasmic fireworks. Instead, they say, sacred spot massage should be viewed as a process that invites a couple into ever greater vulnerability, trust, intimacy, and caring. “Orgasms are part of a natural flow of events,” says Charles. “Don’t go after orgasms, but let them be signposts on the road to sexual wholeness.” The Muirs devote hours of instruction to ensure that their students learn how to use sacred spot massage to integrate the emotional experience of loving connection with the passion of sexual arousal.

But once Charles takes the men off for their separate class, he concentrates on preparing them to serve as sexual healers. First, he coaches each man to honor his partner by making the whole evening a feast for her senses: Tidy and decorate the room. Build a fire. Gather flowers. Dress up. Prepare a special treat of food or drink. Draw her a bath. Give her a massage. Then, he urges, tell her the things you appreciate and love most about her. “Don’t hesitate to invite God—whatever meaning that may have for you—into the bedroom,” Charles tells them with a little grin as he sets up his punch line: “It makes for the best threesome!”

Most of all, Charles prepares each man to give his partner concentrated, loving attention—to remain present with whatever emotional experience comes up for her. “Real presence is far more important than physical technique,” he assures the men. “Get out of your head and into your heart. If difficult emotional stuff comes up for her, it’s not just her stuff; it belongs to both of you.” Charles encourages the men to approach the whole evening as a sacred meditation, an exercise in empathy: “Make the evening a peace offering to your woman and to the collective womanhood of humanity, a healing for every woman who’s ever been raped or molested or demeaned in any way.”

Before sending the men and women off for their “homeplay,” Charles offers them some predictions. “For many of you,” he promises, “this will be the most important night of your life. About 25 percent of couples have ecstatic experiences in sacred spot massage; about 25 percent encounter mostly shadow residues of old experiences that need to be released; and the remaining half have a mixed experience.”

In the morning, when the couples reconvene and begin to share their experiences, Anja validates part of Charles’s forecast: “I would say it was the most romantic time in my life, the most happy moment in my life, and now I am so peaceful. I think I am joining with my higher consciousness in a way I’ve never been before, and I know it’s going to influence my work.” (In class, Anja talks mostly of the spiritual effects of the evening, but in later conversation she also mentions “wave after wave of orgasmic energy” that ran through her body for almost two hours.)

Though none of the other women report transports of ecstasy, all the couples tell stories of increased intimacy, of insights and breakthroughs. For the most demonstratively passionate couple in the group, Tom and Leslie, the exciting shift wasn’t in sexual intensity but in emotional vulnerability. “The biggest gift,” says Tom, “was Leslie crying in my arms, which had never happened before.” Many of the men reveled in their role as giver and healer, delighting in pleasing and nurturing their partners; some also enjoyed an unexpected freedom from performance anxiety.

Not that everyone had smooth sailing. For Susie, the sacred spot massage was painful—both physically and emotionally. “When Bill started to massage my sacred spot, it was uncomfortable, and it brought up all my issues. So I cried and screamed and ranted and raved, and then I cried some more. Bill cried too.” Despite her pain, Susie felt “it was still a healing experience. I’m starting to realize that healing doesn’t happen in one fell swoop. Last night I got a piece of healing.” Turning to Bill, she says, “What I really appreciated was that you were there for me.” Looking back at the group, she says firmly, “He was really there the whole time. And I realized that he has been there for me for a long time; I just didn’t see it.”

Beaming back at her, Bill drawls, “I got yelled at all night, and I loved it. I feel a little guilty. I was supposed to be the giver, and I received so much. After a couple of hours, it dawned on me that I didn’t have to try to quiet my mind. It just happened. Of course, the greatest blessing was that last night was the first time in my life I ever felt like a healer.”

True Tantra?

Despite positive reports from participants in workshops like the Muirs’, some scholars and teachers of more traditional Tantric pathways criticize modern, Western interpretations of Tantra as having little in common with Tantra as practiced over the centuries in India, Nepal, and Tibet.

Tantra began to blossom as a distinct movement within both Buddhism and Hinduism around A.D. 500, reaching its fullest flowering 500 to 700 years later. From its very beginning, Tantra has been a radical teaching that challenged religious orthodoxy. Within Hinduism, Tantra stood in contrast to the Vedic practices of the Brahmins (the priestly caste of Indian culture), who presided over a religion of dutifully performed rituals and strict adherence to standards of purity forever out of reach of the lower castes. Within Buddhism, says University of Virginia religious studies professor Miranda Shaw, Tantra “arose outside the powerful Buddhist monasteries as a protest movement initially championed by lay people rather than monks and nuns.”

It’s never been easy to neatly define Tantra, because it encompasses such a huge, varied, and sometimes contradictory range of beliefs and practices. But first and foremost, although it has produced many philosophical texts, Tantra is a collection of practical techniques for achieving liberation or enlightenment. The word “tantra” itself comes from a Sanskrit root that means “to weave or extend.” Tantra’s practitioners have always seen it as a comprehensive system for extending knowledge and wisdom—for realizing that the whole world is a completely interwoven unity.

Second, far more than most strands of Indian spirituality, Tantra accords great respect to women and to the female aspect of divinity. In the Hindu Tantric view, the world constantly arises from the erotic dance and the union of the divine male (Shiva) and the divine female (Shakti), with Shiva providing the necessary seed but Shakti providing the active energy that brings everything into being. (Tantric Buddhism sees the male principle as the more active, but still emphasizes the importance of women and female energy far more than do other forms of Buddhism.)

Third, Tantra functions not just as an enlightenment practice, but also as a system of practical magic. Certain kinds of Tantra place great emphasis on developing supernormal powers—the ability to fly, to materialize objects at will, to disappear or to become enormous, to be in two places at one time. In fact, the same term—siddhi—can mean either “spiritual perfection” or “supernatural power.” Tantra claims to allow its practitioners to understand the way the world is woven together, and these insights are said to give its adepts incredible powers over the physical world, including their own bodies. In Tantra, the body is seen as a microcosm of the whole universe; the divine female energy is present in the individual person as kundalini, the serpent energy that coils at the base of the spine. Much of Tantric practice centers on awakening and channeling this energy.

Thus, where the mainstream of Indian spirituality tends to regard the world as a trap and an illusion, and to lean toward asceticism and a distrust of the body and the pleasures of the senses, Tantra insists that the world is the manifestation of divinity and that all experience is potentially holy. This fourth trait of Tantra is perhaps its crucial characteristic: Rather than regarding the everyday life of the body and its desires as a defilement to be purified and transcended, Tantra regards embodiment as the fortuitous and necessary vehicle for enlightenment.

Tantra’s appreciation for the body made it into an enormous laboratory where generations of yogis experimented with ways to purify their bodies so they could carry the enormous energy of awakened kundalini. According to noted yoga scholar Georg Feuerstein (himself a practitioner of Tibetan Tantric Buddhism), “Hatha yoga grew straight out of the concern in Tantra for creating a transubstantiated body—a body that was totally under the control of the yogi, that he/she could manifest and de-manifest at will, a body that was immortal, like the body Taoist mystics sought to develop.”

Eventually, the focus on purification led much of yoga practice toward asceticism. But much of Tantra headed off in unascetic directions. As you might expect in a magical tradition that sees the cosmos as the constant product of sexual intercourse, the Tantrikas (Tantra practitioners) didn’t just explore sex as a metaphor; they made it a crucial activity in their spiritual path. Viewing all of life as holy, they rejected the traditional Indian tendency to categorize activities and experiences as either pure or impure. The most radical Tantric groups convened their rituals in the charnel grounds, meditating atop corpses, smearing themselves with the ashes of the dead, eating and drinking from cups fashioned from skulls, and indulging in all the activities most condemned by mainstream religion: eating meat and fish, consuming aphrodisiacs, alcohol, and other drugs—and engaging in ritual sexual intercourse as a way of raising and exploring the movement of heightened energies.

It’s true that, as scholars have pointed out, only a small proportion of Tantric texts—less than 10 percent—deal with sexuality; well over half the texts focus on the use of mantras, while others focus on the worship of deities and the creation of visual aids to meditation and magic. In addition, over time more conservative Tantric groups (known as “right-hand Tantra”) minimized the most daring practices, transforming forbidden activities into metaphoric representations of spirituality rather than actual ritual practice. (More radical groups—practitioners of “left-hand Tantra”—tended to remain underground, safe from attacks from the mainstream of Indian culture.) But from the first outraged denunciations by scandalized Brahmins centuries ago, right up through the West’s recent curiosity, outsiders’ fascination with Tantra has always focused on sex.

It’s Not Just Sex

Feuerstein believes that Neo-Tantra—his term for Western versions of Tantra that focus on sex and relationship—”can do a great deal of good for people who have been raised in an atmosphere that represses and denigrates pleasure,” and that “it provides meaning and hope for some of those who have outgrown guilt-ridden puritanism and conventional sexuality.” However, he expresses concern that many teachers of Neo-Tantra have neither studied Tantric texts enough to understand the tradition clearly nor received “proper initiation by a competent Tantric guru.”

Although ancient texts are chock-full of dire warnings of Tantra’s risks, Feuerstein doesn’t believe gaps in Western Tantra teachers’ education place students in any serious danger. “Unless you are instructed by a true guru—in other words, a teacher who has succeeded in raising his or her own shakti—you aren’t likely to raise dangerous energies that could unbalance you physically or mentally,” he says.

But Feuerstein does fear that Neo-Tantra practitioners can easily get caught up in egoistic motivations, rather than learning to transcend the ego. He claims that in more traditional Indian Tantra, adepts never started by opening the second chakra—the sexual center—but by opening the fourth chakra (the heart) or the sixth chakra (the third eye, seat of intuitive wisdom). “Only when the guru was sure the adept had established pure intention and strong control of energy was the enormous power of sexuality invoked,” he says, adding that perhaps the greatest danger of Neo-Tantra is that practitioners will fool themselves into thinking they’re having “spiritual” experiences when all they’re doing is enjoying a blast of increased prana (life energy). Feuerstein fears that by confusing physical pleasure with spiritual bliss, many Neo-Tantra practitioners may miss out on the deepest rewards of Tantra—the ecstasy of union with all Being.

Rod Stryker, a teacher of right-hand Tantra who studied with Tantra master Yogiraj Mani Finger and is also an initiate in the tradition of Tantric master Sri Vidya, echoes many of Feuerstein’s concerns about contemporary Western Tantra. “As a yoga teacher,” says Stryker, “I’ve worked with a lot of people—essentially, I’ve treated a lot of people—who were deeply scarred by the experience of trying to direct sexuality, cloaked as Tantra, as a tool of enlightenment.”

According to Stryker, maithuna—the sexual techniques of Tantra’s left-hand path—were traditionally regarded as catalysts to awaken psychic energy, so powerful that some schools even regarded them as shortcuts past more basic techniques like asana and pranayama. But right-hand paths, says Stryker, never saw sexual techniques as substitutes for the gradual, progressive use of asana, pranayama, and meditation. “The danger is that if someone’s nadis [the body’s energy channels] are not as open and clear as possible, the sexual techniques can create psychic turbulence and have a dis-integrating effect,” Stryker says. “It’s very likely,” he notes, “that people who go do a Tantra weekend have done very little of the foundational work of asana and pranayama. They may experience a lot of energy moving, but if they are neurotic and they start to awaken vital energy, they can wind up empowering their neuroses.”

Like Feuerstein, Stryker stresses the difference between pleasure and bliss and the need for a guru. He points out that the approach to Tantra he has been taught delineates three distinct stages of ecstasy—physical, psychic, and spiritual. Only in the second stage of ecstasy does a seeker achieve not just heightened sensory awareness, but also the necessary energy to change his or her life to align with an awareness of spirit. (In the third stage, once the seeker has awakened the state of consciousness associated with each chakra and can apply the appropriate state to any situation, ecstasy becomes constant.) Without the guidance of an experienced Tantric guru, Stryker fears, students may get stuck at this first stage.

Stryker suggests any Tantra student should examine their teachers with two questions in mind: “To what extent do the teachings live within the teacher and in their relationships? And to what extent do the teachings live in the lives of this teacher’s students?” Whether or not Western Tantra teachers are equipped to be full-fledged gurus, says Stryker, he hopes they at least educate their students to realize that physical ecstasy is only a fraction of the gifts of Tantra.

Whatever the limitation or perils of Tantra as it’s now being adapted for Western consumption, its advocates are passionate about its ability to change lives—and, by extension, to change the world. Margot Anand, for one, says, “Once you’ve opened your five senses, once you’ve brought all the levels of yourself into engagement with life, you may find yourself transformed. You may never be willing to go back to a life that doesn’t leave room for your creativity, your playfulness, your capacity for joy.” And Charles and Caroline Muir urge workshop participants to consider that they’re not doing this work just for their own benefit, but also so they can bequeath a saner, healthier sexual legacy to their children and grandchildren.

In answer to criticisms from more traditional Tantrikas, Charles insists that the Tantra he and Caroline teach is in the spirit of ancient practices, even if its outer form is different.

“We seek to awaken and integrate the dormant energy of the chakras,” he says, “just as they did in ancient India.” Explaining his adaptations, Muir claims “You don’t need all the trappings of Indian culture and philosophy to experience the benefits of Tantra.”

Muir readily admits that modern Western Tantra may not look much like its ancient antecedents. But, citing the enormous historical variety of Tantra practices, he points out that “like yoga, Tantra has been born again and again, age to age, based on people’s needs at the time.” His version of Tantra, he thinks, addresses major needs of our current place and time: restoring proper reverence for women and the feminine; finding an appropriate, beneficial outlet for male “warrior” energy; and healing the rift between men and women.

On the last morning of the workshop at Rio Caliente, as the participants gather to share their thoughts on the week, no one seems especially concerned with whether or not they’re on their way to enlightenment. They’re too busy basking in the benefits the week has brought them. In contrast with the first evening of the workshop, all the couples snuggle together, some holding hands, some smiling into each other’s eyes, some just sitting in a relaxed, companionable silence.

“I got all I had dreamed might be possible, and more,” says Merle. (Unable to resist the joke, someone ad-libs, “Plenty of bang for the buck, huh?”) Merle’s partner Anja, who had described the sacred spot massage as the happiest moment of her life, says the workshop renewed her commitment to the hatha yoga practice she’d dropped years before, and several other participants echo her determination to continue with yoga after returning home.

The workshop seems to have inspired many of the participants to eloquence. Stan, the 67-year-old grandfather and fiancé, reads a poem of appreciation for his partner that leaves almost everyone in tears. Matthew, the Zen-practicing doctor, says he sees all the workshop participants as “a vast, beautiful, green healing field of love,” with Charles and Caroline as the cultivators. And his partner Amy vows that she now knows “Nothing is more important than learning how to love each other better.”

When Bill’s turn comes, his characteristic directness lends the simple poetry of economy to his words. “This week,” he says, “tore down walls it took Susie and me 25 years to build.” Looking at the pair as they sit with their legs entwined, occasionally stealing glances at each other like shy teenagers just discovering love, Caroline quips, “OK, you two win the Most Improved Campers award.” As the laughter dies down, Susie says, “I’ve been on a healing journey for a long time, and I often thought I would have to leave Bill behind. This week I discovered I have a partner in healing.”

Article First Posted on Yoga Journal